In my last post I announced the release of the book Did Quaid-e-Azam Want to Make Pakistan a Secular State?. I’m reproducing the foreword below, in which I explain how the book prompted me to write Secular Jinnah.

In my last post I announced the release of the book Did Quaid-e-Azam Want to Make Pakistan a Secular State?. I’m reproducing the foreword below, in which I explain how the book prompted me to write Secular Jinnah.

But first, a note for those who are unfamiliar with the debate over Pakistan and are wondering about the title.

On the word ‘secular’

Simply put, the word ‘secular’ in the above title is really a synonym for ‘materialist’. Many Pakistanis don’t differentiate between the two concepts, because they see materialism as the final outcome of separating religion (and its moral values) from state affairs. This is why many Pakistanis will say they have no problem with the concept of equality before the law (usually identified with a secular state) and yet won’t identify themselves as secularists.

So, onto the Pakistan question. Pakistanis have never agreed over whether Pakistan was meant to be a ‘secular’ (materialist) state or an ‘Islamic’ one (that is, a religious state). In my books, I have tried to show that Pakistan (in the eyes of its founders) was not meant to be either a secular or a religious state, nor was it supposed to be a paradoxical mix of religion and secularism. So if it was none of the above, what was it? The answer can be found only when we understand what secularism and religion respectively mean. In short they are practically two sides of the same coin, in that one focuses on materialism, and the other on spiritualism. That makes both of them not so much wrong as incomplete. And yet we can’t complete them by combining them, because the two are also totally incompatible for reasons I need not go into here. At any rate, a combination or synthesis of religion and secularism is also impossible. In my books I have described a fourth possibility in line with the Quranic view of reality, which encompasses both the material and the spiritual simultaneously – not as two separate things combined, but, to borrow from Iqbal’s description of Islam, “a single unanalysable reality which is one or the other as your point of view varies” – a bit like the uncertainty principle in quantum physics. Parwez operated on the same matter-spirit oneness principle in his book The Qur’anic System of Sustenance.

Purchase details (including discounted rates for both this title and The Qur’anic System of Sustenance) can be found if you scroll to the end of this post.

Without further ado, here is the Foreword.

—————————————————————————–

FOREWORD

This booklet is of special significance to me. It is directly responsible for the publication of my first book, and indirectly for my second as well. Indeed, this short publication can be credited for practically launching my writing career.

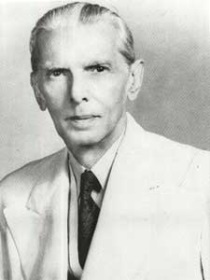

Avid readers of Pakistani history will know that Chief Justice Muhammad Munir’s From Jinnah to Zia (1979) is said to be one of Pakistan’s all-time best sellers. This is because Munir was the first to openly declare that M.A. Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, was a ‘secularist’ (i.e. he advocated the separation of religion and state as in modern democratic states). Coming as it did from a former Chief Justice, this declaration carried much weight for Pakistani readership, and indeed, as Munir testified in his book, across the world the as well.

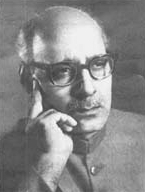

G.A. Parwez, who had known Jinnah personally and had been his counsel on matters relating to Islam, wrote a rebuttal in Urdu in 1980 soon after the second edition of Munir’s book was released. The English translation of that text can be found in the following pages. However, the original rebuttal missed one vital piece of information; and since this missing information was the catalyst for some completely new and important research I conducted some twenty-five years later, I would like to share the details for the benefit of the reader.

I originally came to translate this booklet not for Tolu-e-Islam, but for my father. In 2003 he had published a book titled Quran aur Pakistan (Sheffield: Bazm-e-Ilmofunn), containing his own Urdu poetry alongside a collection of G.A. Parwez’s writings, and the text of this booklet appeared as one of its chapters. My father and I worked together on the English translation, and in the course of crosschecking the references, I obtained a copy of From Jinnah to Zia. This was when I first noticed a quote not accounted for in Parwez’s rebuttal.

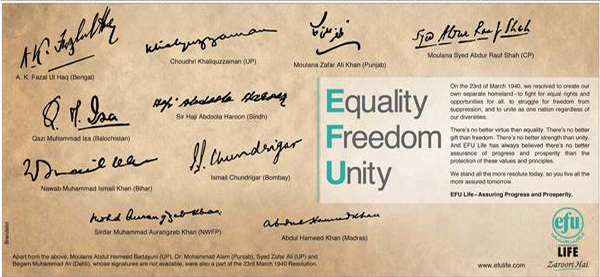

Parwez has written that in From Jinnah to Zia Munir relied on two pieces of evidence to support his claim that Jinnah was a secularist. They are:

1) Jinnah’s statements against theocracy

2) Jinnah’s inaugural address to the Pakistan Constituent Assembly, on11 August 1947

However I found that Munir had actually relied on not two, but three pieces of evidence. The third and most important piece of evidence that Munir produced (and which he cited several times for emphasis) was Jinnah’s interview to Reuters, dated 21 May 1947 (dated incorrectly in Munir’s book as 1946). In this interview, Jinnah supposedly said that he envisioned Pakistan as a ‘modern democratic state with sovereignty resting in the people’ (Munir 1980, p.29). He stressed that the words were at odds with the Objectives Resolution, which states that ‘sovereignty rests with Allah’. At this point, since Parwez had not addressed the quote, I decided to try and find the original source to look at the context in which it might have been used. When I did obtain it around a month later, it emerged that not only was the date wrong, but the quote was actually a fake. Since that time, I have referred to it as the ‘Munir quote’.

This was just the beginning of my journey in learning about the Pakistan story. At first I intended only to write an article on this quote, but I had underestimated the significance of what I had uncovered. Munir’s quote, along with the two pieces of evidence that Parwez had highlighted, had long become a formulaic argument copied virtually verbatim time and again by every kind of writer, from the journalist to the historian, and accepted blindly as fact, without question. No one had thought to check on the original source and in fact no one even seemed to know or care as to where it originated. My first book, Secular Jinnah: Munir’s Big Hoax Exposed (2005) was the unexpected outcome of my first round of research, and here I wrote that the original source was probably Munir’s From Jinnah to Zia. But I was later to discover that this was not the original source of the quote. At any rate, my book was short and it hardly touched on Pakistan’s founding history. Over the next five years, my research continued and intensified, and I resolved to release a revised edition containing, among other things, updated information on the misconceptions about Jinnah and the Pakistan story. Instead I ended up writing an entirely new book. This was a complete political biography on Jinnah which also covered my updated research on the Munir quote. By the time I released Secular Jinnah & Pakistan: What the Nation Doesn’t Know in 2010, I had learned that the Munir quote had its origins not in Munir’s 1979 book, but in another famous publication authored by Munir: The Report of the Court of Inquiry Constituted under Punjab Act II of 1954. It is better known as the Munir Report, since it made Munir a celebrity and he became Chief Justice of the Federal Court soon after the inquiry ended. Following the Munir Report, the first time that the fake quote was used as supporting evidence for a secular Pakistan was in Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly in August 1954. This quote had never been cited before, simply because it didn’t exist; and so this was the first time that the secularist politicians of Pakistan succeeded in silencing their opponents outright. Thereafter Munir’s quote was accepted as a legitimate piece of evidence for fifty years.

As for Quran aur Pakistan, although we began its translation in 2004, we were unable to publish it due to technical issues, and subsequently this also delayed the publication of this booklet for a long time. I am happy to know that the booklet at least is finally going into print. It may be one of Parwez’s lesser known works, but without it, the Munir quote may not have come to light for another fifty years. For that reason, it certainly has great historical value; but to me personally, for my own reasons, its worth is immeasurable.

Saleena Karim,Nottingham

23 August 2012

—————————————————————————–

Did Quaid-e-Azam Want to Make Pakistan a Secular State?

Available now at CreateSpace

(Also available now at Amazon)

5.99 USD (CreateSpace & Amazon.com)

4.99 GBP (Amazon UK)

Paperback, 64 pages

Published by Islamic Dawn Society and Tolu-e-Islam Trust in association with Libredux Publishing. Translated and edited by Saleena Karim & Fazal Karim.

Get 25% off this book if you purchase from CreateSpace, using the following discount code at checkout (limited offer):

Go to this page

Discount code: GWRCFWQK

—————————————————————————–

Get this book 25% off too

Get this book 25% off too

You can also get The Qur’anic System of Sustenance at the same 25% discount if you apply this code at CreateSpace:

Go to this page

Discount code: AN3UM9VX

In my

In my