My brother recently pointed out to me that with the publication of Khurram Ali Shafique’s Iqbal: His Life and Our Times, I can now claim to have covered three great Muslim personalities of the last century: Jinnah, Iqbal and Parwez. This was something that had never crossed my mind before.

My brother recently pointed out to me that with the publication of Khurram Ali Shafique’s Iqbal: His Life and Our Times, I can now claim to have covered three great Muslim personalities of the last century: Jinnah, Iqbal and Parwez. This was something that had never crossed my mind before.

Jinnah and Iqbal rank among the most important figures for Muslims in the Indian subcontinent, while Parwez has had an enormous impact that has yet to be appreciated whether among academia or in the public eye. For myself personally however, the fact that I have had the good fortune to cover these particular three is especially significant. Have a look at the three men in turn, and I hope you’ll see what I mean.

First, each respectively represents one of the three Cohesive Ethics principles. Visiting them in chronological order of my publications:

Parwez: Justice

My earliest writing work was the translation of my father’s Quran aur Pakistan, which was a book containing his poetry and a compilation of various writings from G.A. Parwez’s work. One of the chapters from this book was a reproduction of a pamphlet of Parwez on Jinnah that I eventually published many years later. And of course, my work on this pamphlet also led directly to my work on Jinnah.

Parwez was a prolific writer, but arguably his most important contribution as a scholar was his 1955 book Nizam-i-Rabbubiyyat (System of Divine Sustenance), an economic treatise that took a holistic and groundbreaking view of Quranic terms normally identified with capital interest and religious charity. My father and I have translated this book under the title The Qur’anic System of Sustenance. Parwez’s strong emphasis on social justice and criticism of capitalism in that book has led even some of his supporters to wrongly think he was a closet communist – despite the fact that he described communism as “a grave danger to humanity” and went to great lengths to reveal the stark differences between materialist communism and his Quran-inspired work. In any case, Parwez’s work in this field makes him an unequivocal representative of the justice principle.

Jinnah: Unity

My first full book was on M.A. Jinnah, and so was its better known sequel, Secular Jinnah & Pakistan.

Jinnah represents the unity principle. No, he practically personifies it. He was dubbed the “ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity” in his early political career; and later, both as the leader of the Pakistan independence movement and as the founding father of the country, “unity” remained his watchword both for “Muslim unity” and for a Pakistani nationality that encompassed its multicultural population. The Pakistani national motto “Faith, Unity, Discipline” was coined by Jinnah during the Pakistan movement. The word “unity” turns up countless times in his speeches and statements and is probably the word that he used more than any other.

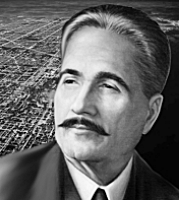

Iqbal: Liberty

I wrote a full chapter on M. Iqbal in Secular Jinnah & Pakistan on the crux of his philosophy. My imprint Libredux Publishing has also published two books on his philosophy: 2017: The Battle for Marghdeen and Iqbal: His Life and Our Times. Iqbal’s references to the three principles of “equality, solidarity and freedom” are of course the “muse” of the Cohesive Ethics Theorem in Systems.

Iqbal undoubtedly represents the liberty principle owing to his emphasis on human will and action, and his calls for a “reconstruction of religious thought in Islam” in the famous lectures of the same name. He wanted Muslims to revive the long-abandoned practice of ijtihad (lit. “strive”), which amounts to freeing the Muslim community from the shackles of tradition so it can learn to actively adapt with the needs of its time. He dedicated his fifth lecture solely to this topic, describing ijtihad as the “principle of movement”.

Second, these men have some striking similarities with the characters from Systems who also represent the same respective principles.

Parwez and the Peace Man

Though they are worlds apart, Parwez and Peter Manner (the Peace Man) have some uncanny parallels. Both are lone warriors. Both possess keen insight into the failings of humanity, and its potential. In his writings Parwez calls for a revolution against the three forms of tyranny mentioned in the Quran, while Peter is on a crusade against an unnamed “them” – that is, E3, who represent the same three evils.

Both are totally committed to the idea of total justice, though Peter takes it to the extreme: He kills one “worthless” criminal for every friend he has lost in his previous life, and returns every single penny he has taken from the innocent people he robs. Parwez’s work on economics, despite not being nearly as dramatic in practice, is nevertheless driven by a similar level of conviction in the possibility of absolute justice. (And incidentally, Peter’s past life incarnation was also an economist). Both Parwez and Peter are absolutely determined to see their causes through, irrespective of how others may respond to them. Parwez’s sheer tenacity and courage easily match Peter’s, as he was more forthright in his calls for religious reformation than even Iqbal, literally risking his life in upholding his views in a hostile religious environment.

Iqbal and the Shaman

The strange similarities between Iqbal and Hitoshi Katayama are too numerous to list in full. Iqbal’s poetical inspirations from Revelation include David (The Persian Psalms) and Adam (in various works including Javid Nama), the namesakes of the twins who are tied to Hitoshi (also known as the Shaman in Systems). Both Iqbal and Hitoshi are poets, and both possess musical talent. Both have complex, larger-than-life personalities. Some of the things they say are incorrectly interpreted as being esoteric. Both are frequently accused of ambivalence and contradiction – though this accusation is more justified in Hitoshi’s case – and both are aware of, and comfortable with, being a mystery to others.

Each of the two also fulfils his “destiny” in an apparently ironic way – Iqbal through his choice of the seemingly “secular” Jinnah to lead the Muslims of India, and Hitoshi through his decision to destroy the only proof that the Systems Experiment was a success. This reveals how they each symbolise the conflicting nature of the liberty principle. Both also acknowledge their dark sides, though in different ways: “I have a certain amount of admiration for the Devil,” says Iqbal, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, in his first English-language lecture in 1908. Hitoshi would definitely return that remark with his characteristically devilish smile. Indeed, an early edit of Hitoshi’s song This is my Fate in the novel contained the lyrics “blessed in the Devil’s light”.

Jinnah and Agent Numbskull

Jinnah and Aaron Lloyd (named after the Prophet who also represents unity) both uphold the unity principle in precisely the same way, through a shared sense of inclusiveness. Aaron asks Hitoshi to join forces with him to try and defeat their common enemy, even after learning the truth about Hitoshi’s background. Similarly Jinnah asked Muslim religious and political leaders alike to set aside their differences in order to rally around a common goal, though he was well aware of their shortcomings.

Jinnah also shares what Hitoshi rudely calls the “numbskull” trait with Aaron – that is, both Aaron and Jinnah come across as cold and unreadable, one by virtue of a cranial chip, the other by his behaviour. Yet in fact both are deeply compassionate underneath the surface, and are really using the system to fight the system. Jinnah uses his British training in constitutional law to fight against the British Raj, while Aaron is an agent working for, and secretly fighting against, the very organisation responsible for killing his father and destroying his legacy. And on that note, both Jinnah and Aaron stand against benevolent dictatorships.

Finally, a disclaimer.

The connections between these three makers of history and the three leading men from Systems are remarkable, but by no means were any of the fictional characters consciously (or unconsciously) inspired by the historical figures. However, one of the three men did directly inspire another character in Systems, namely the eccentric professor Dr. Hanif Omar, the man behind the Cohesive Ethics Theorem and the Systems Experiment.

I’ll leave it to you to decide which one it was.

If you can think of any other links between the three men and the characters that I have failed to mention, please let me know here in the comments.

In my

In my